The Gulf War – A Personal Memory Mark Paveley

It was all rosy that Summer

Early Summer 1990, halcyon days in BAOR, the lull between relentless exercises across Westphalia in Germany consisted of painting trucks, greasing springs, sweeping floors. For me as a young technician I had recently

moved from an Armoured squadron to HQ Squadron and was in charge of an Electronic Repair Vehicle steadily working through thebacklog of broken kit to get it ready for the Autumn exercises. No doubt in feet of snow again, perhaps a frozen face as commanderof a tracked vehicle, a 35-tonne sledge on occasion, whilst warming the next meal on the louvres that were keeping the lower half of me toasty at the same time. All interspersed with BBQs, sports, fun,wonderful family time. Stationed in San Sebastian Camp at the far end of the Möhnesee Dam (of Dam Busters fame) was a delightful place to enjoy outside the wire, a beautiful setting. The camp was split in two, the bottom camp a mix of a Canadian WW2 prison where one of the squadrons was based as well as very modern workshops and garages, the top part of camp was all single storey singles accommodation, Divisional HQ and a smattering of garages too, no mod cons to be seen. Living in Soest with my wife and months old son we enjoyed family days at 'the patch' and were having a whale of a time. This was the rhythm of BAOR, and specifically my Regiment, the mighty 3rd Armoured Division HQ and Signal Regiment (3ADSR).

Figure 2 - My house, Christmas 1989, all blokes deployed

Figure 1 - 3 Sqn, 3ADSR

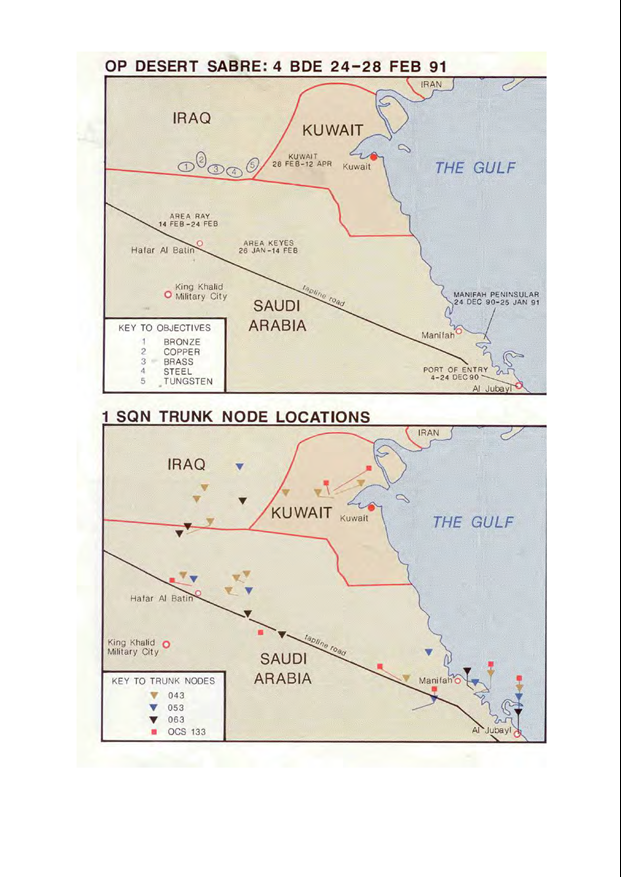

Some context on my job. Specifically, for this deployment, I was part of Trunk Node 043, each Trunk Node made up of about 15 communications and power vehicles and around 50 personnel. Trunk Nodes were the heart of asystem

called Ptarmigan, a bit like a series of phone and data switching centres using radio links to create a chain across hundreds of miles when linked together, and at points links extended to HQs where the telephony and data equipment buzzed all day as the various levels of HQ coordinated, planned and gave out orders. We also had mobile telephony and data capabilities – yes even in1990/91. That was called Single Channel Radio Access (SCRA) with Centralsto blast out cells for Terminals to

connect to, this hooked into the Ptarmigan System too and with the addition of Satellite Links for the first time a Terminal user could phone from a moving vehicle and talk to the Prime Minister if warranted and all totally encrypted, pretty impressive stuff. Now don’t think these were like today’s mobile devices, these were hefty bolted-in Terminals operated from vehicles, although did lead to many of the break-throughs companies such as Vodafone and BT took forward. I will say that the Centrals gave off such high power that nobody wanted themclose by, with the right (or indeed wrong enemy) it was an easy target to electronically find, lock onto, and takeout. Thankfully the enemy this time round never got the chance!

Figure 3 - SCRA(T), a ‘mobile phone’

And We’re Off

Then some dictator none of us gave a second thought about decided to invade Kuwait, and the touch paper was lit for the next 9 months or so. August continued with little change for us oiks, am sure the HQ were embroiled inmuch planning unbeknownst to us. September came and activities ramped up suddenly, and within a week or so a large group of us were bussed to Lippstadt for deployment briefings and preparation. I say bussed, more crammed into the 'green limousines' i.e. 4 tonne trucks with (un)comfortable wooden benches, still, not a long journey thankfully. After a few days it all changed again and my Regiment was stood down.

"Well Cpl Paveley you'd best go on your Det Commanders course hadn't you!" said my Troop SSgt. So off I went to that promotion course held at the 13th Signal Regiment camp near Birgelen, close to the Dutch border. So followed weeks of getting run ragged, parades, marching, drill, field skills, and very long days ahead, yippee! As it happens, I had a great time on the course and was top student with my best mate second, plus it was great training for what was to follow. Into the last week around the middle of November, all the nonsense done, we were paraded to be told to get back to our Unit without delay, we were to deploy to the War after all. Now, in those days without delay on German autobahns meant a blurry 120-130 mph journey for a good part of it, like you-know-what off a shovel. Anyway, we got back, straight into briefings and then readying our vehicles (including painting them a sand colour) and communications kit ready for them to be loaded onto civilian ships at Emden between 29 Nov-6 Dec 90 setting sail for Al Jubail (sometimes written Jubayl). For a couple of weeks we had briefings, up to 6 injections I can't remember the names of and the start of Nerve Agent Pre-treatment Set (NAPS) tablets, thechemical threat was real.

The advanced party left 14/15 Dec 90 with my Trunk Node flying out to arrive on 20/21 Dec 90 just in time for Christmas courtesy of Crab Air (RAF) and straight into what felt like a furnace after Winter in Germany. The atmosphere was almost holiday-like for a few days including the traditional food throwing Christmas Dinner and part of the day spent at Pearl Beach – all in the name of acclimatising, then it became deadly serious!

Our trucks arrived on 26 Dec 90 and we switched into full-on military mode very quickly, no one was mucking about now, we set off immediately for the Manifah Peninsular to check equipment and conduct a communications check.

Figure 4 - Christmas in Al Jubail

On 3 Jan 91 off we trundled up the Main Supply Route (MSR) to set up a comms link on top of a Jebel (a large flat-topped hill/small mountain). The drive was uneventful, getting on top of the Jebel took a mammoth effort,

Bedford trucks carrying a further 12 to 14 tonnes of communications kit is OK on roads, not on sandy slopes. We had to walk alongside, using shovels to dig in metal tracks repeatedly to aid the grip. That was a slow and energy sapping day, towards the end made a wee bit easier when a Saudi army recovery vehicle helped winch the lastand heaviest vehicles up.

Figure 5 - Me and Martin on the Jebel

We set up our Trunk Node, then dug in, literally. We dug shell scrapes, built defence lookouts on the cliff edges, and covered our vehicles in Chemical Agent Resistant Material (CARM) under the camouflage nets of course. And so, a shift pattern of maintaining comms and guarding our site became our new rhythm for the next couple of weeks. Below our cliff top position there was a Bangladeshi unit and we struck up an accord with them. We thought our kitwas not the best then (no body armour or hard vehicles protected from missiles), the Bangladesh unit was like something from a Rudyard Kipling book, just the old-style canvas tents and compete with silver service for theofficers, I am not joking!

We made friends with our comrade soldiers and when time allowed played volleyball with them, all whilst keeping our NBC respirators at our waists, just in case. The reports of the use of sarin gas having been used focused our minds, we took it seriously and never questioned any order I can remember.

Mid to late January (I think that's about right) we tore down and headed further north toward the Iraqi border. After establishing communications and having dug in again we had about 2 weeks of training including night moves, following each other’s convoy lights (a white plate with a dim light just under the back of our trucks) and aiming for lumi sticks where the RMP had convergence and navigation points. We also extended the convoy lights to a red light on top of each vehicle so we could be seen from the air by coalition aircraft, there were not any fancy electronics to help with this in those days, it seemed to work for latter parts during the fighting phase, at least for us, for others not so lucky. Friendly fire, doesn’t sound right does it? Well, it happened, even British on British!

By this stage a few people had been sent home due to injuries and running short of drivers I found myself with an HGV to drive (no license!), 10 minutes familiarisation followed by incredibly focussed night driving with no normal lights, needless to say I learned very quickly. We were practising with live grenades, zeroing our weapons, making sure everything was as spot on as it could be. Checking it all over and over again. One day a truck load of us hadreached a local Saudi Town to use a phone to call home, “reverse charges from Saudi please”, we all got through for a few minutes at least. Whilst there a scud missile went overhead, or so we thought, an Iraqi missile. We mounted up and sped back to our column, one of the hundreds of columns waiting to move forward through thebreach.

It’s Really Happening

Around 22-24 Feb 91 MLRS started with what seemed a downpour of munitions into occupied Iraq, that and thecluster bombs being dropped made for a sight one can never forget, we could see the bright bursts in the distance. This was when the coalition ships were also sending hundreds of tonnes of missiles at the enemy, the War was properly on. You see this sort of thing in films, experiencing it is simply strange, a strange sense of detachment from the reality of what your eyes are seeing and your brain is processing. The order came, we were off, fully kitted in NBC suits with respirators at the ready we trundled through the breach on 24 Feb 91, a path having been cleared through the minefields before us, carefully following the markers laid out. We could hear other vehicles causing anti-personnel mines to explode resulting in donning out respirators and rapidly blowing the stale air out as taught. The 9 second rule became 4 or 5 in practise, amazing how you react knowing chemical munitions had been laid and used by the enemy!

Figure 6 - As we crossed the breach

Figure 7 - column following my truck through the breach

We arrived at our first location in Iraq and started to set up whilst digging in again, very rapidly we packed up and moved again, this happened twice within 10-12 hours, things were happening at some pace. We passed queues of people at cookhouses and thought that weird, turned out they were Iraqi prisoners already surrendered or captured, and being fed. Now, a Wadi is a dry riverbed in the desert usually full of very soft sand. Don't drive in or near them, it is bloody hard work to dig out again! Some blisters resulted I can tell you!

Figure 8 - Me and Steve in Noddy suits

At last, we stopped and set up again, maybe by the 26 Feb 91 now, who knows? We dug trenches and shell scrapes and provided thecommunications we were trained to do. Maybe that night, maybe another, I was in guard in the middle of the night using the night vision goggles to scan in front of me when my whole view became a dark blur, odd I thought, the batteries are dead, dammit! I lowered the sights, the smell hit me then I must have jumped like the old woman from Tom and Jerry. Right in front of me a blooming great camel, crikey they are silent movers. My reaction caused the bugger to run off, then my heart slowed its pace a little. The two of us in the trench just looked at each other and laughed, that laugh that is a mix of fear, strangeness and relief all at the same time.

Figure 9 - Digging in, again!

After another day or less we set off and crossed into Kuwait, trying to keep up with the rapidly advancing brigadesall the time. Another couple of stops later we reach our final stop in Kuwait, the ceasefire called on 28 Feb 91. And a huge sigh of relief overcame us all having moved 6 times in 4 days, very little sleep for anyone. Moving is not just a case of driving off and parking up. More like; comms closed down, camouflage pulled in, kit packed away, defences loaded, guarding all the time.

Then drive to the reach a destination; dig in, camouflage up, guard duty, comms in, cup of screech to celebrate(if you know you know!). And all in extremely hot temperatures.

Figure 10 - Air defences!

After the Ceasefire

In the days that followed we carried on delivering communications, settled into a little routine but always with an eye on potential danger, there were booby traps left on enemy vehicles and lines – nasty, and skirmishes going on around us. And on top of that Iraqi soldiers were emerging from their locations to surrender, we had two just wander across the desert to us, forlorn and desperate, I’ll never forget their faces. Of course, we looked after them and after a day or, so they were taken to a central location to be with their own comrades. At another

Trunk Node two blokes went to fetch fuel, returning with 400 prisoners, and no fuel, crazy. As a systems technician my job was to keep the comms kit working and fix it as needed, the Ptarmigan system in my view was one of the best examples of solid engineering I have come across, the electronics did their job, the mechanical bits suffered most, even the cables.

Figure 11 - off somewhere I cannot remember

3 Phase cables suffered in the near 50oC heat, the rubber was melting including the inner sheaths for each phase causing leakage and failure. Digging into sand and burying is a very useful way of getting to rapidly much cooler levels, useful if you’re ever stranded in the desert! Duly we dug the cables in as much as we could, but they had to come out and up to the vehicles at some stage – I had learned a lot in how to bypass systems to get comms powered up, some you would never do in ordinary circumstances!

Mad flies do exist! Above about 45oC it seems that Kuwaiti flies turn into hungry animals and will bite any part of you they can find, learned a lesson there. Our OC also learned a valuable life lesson, don’t use cooking oil for sun cream, the dozy twit tried to speed up the tan before going home and ended up in a Field Hospital (he was ok after a few days of embarrassment and pain, thankfully) and on his triumphant return had a rousing reception, every word you could think of to berate him! This was all in good humour; we were glad he was ok and glad the War waseffectively over. Another delightful aspect of looking after ourselves was ‘poo duty’.

We used metal bins that each day were dragged off to a pit, doused in diesel and set alight along with other detritus of the day. It’s odd that my abiding memory is not the smell, rather the sound, was a bit little pouring milk on rice krispies, snap crackle and pop. One usually received this honour for some misdemeanour in the previous day, even if made up. We all knew it needed doing, no-one refused. After it had all calmed down and there was a time to reflect and relax, we came across a great deal of abandoned and destroyed enemy equipment and had a chance to see what had happened to Kuwait City itself.

Figure 12 - I love helicopters

Figure 13 - All the mod cons

Figure 14 – Me relieved it was all over

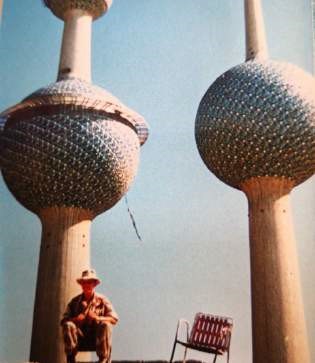

Figure 15 – Me in Kuwait City

Figure 16 - Kuwait City, British Embassy

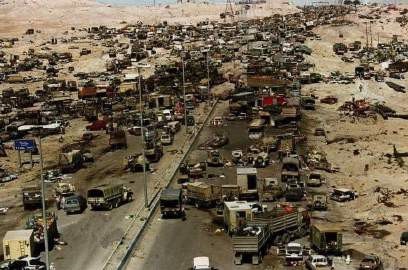

Whilst resupplying and also the as we moved onto the highway to return to Saudi Arabia, I will forever remember the sight of the ‘Death Highway’ or ‘Bomb Alley’ where Iraqi soldiers had fled the City to be blown asunder. I saw other awful sites that are tattooed within my memory, and that is where they’ll stay, no photos thank goodness, truly terrible. This is not a great thing to witness and a solemn reminder of how awful war really is, for many of them they were conscripts forced into an event by an evil man.Reports vary wildly for how many Iraqi soldiers died from about25000 to over 300000, many civilians also perished at the hands of both Iraq (including the Kurds killed by sarin) and the Coalition, we must never forget the cost of such events not only during but afterwards too. I feel for the UK military who had the job of creating mass graves and using heavy machinery to move bodies, I fear that many were traumatised by that, I hope they have received the help they undoubtedly needed.

We made our way back to Saudi Arabia around mid-March 91, to prepare the vehicles for their return toGermany, and left in groups over a period with some not returning until May 91. For me it was a rapid return as explained further below.

Figure 17 - Death Highway, Kuwait City

Medal Recognition

The medal second from left was for Op Granby, during the War if one also servedin Kuwait for the requisite number of days, we were awarded the GSM (General Service Medal) for Kuwait. That is the top bar on the left hand medal, the bottom bar is for N.Ireland. In other words the two bars signifies two GSM medal awards. Ideally the Kuwait bar should be at the bottom as it came first by date, however most of us did not learn of this until fairly recently so I have attached it for now with my bestest sewing skills, it’s expensive to have medals mounted so I’ll wait until the OBE comes along J

The Kingdoms of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait also awarded medals in recognition of our involvement, we cannot wear them with our UK medals as one would expect, mine take pride of place in a display cabinet at home.

Figure 18 - Gulf War Medal and Kuwait GSM

Figure 19 - Kingdom of Kuwait Medal

Figure 20 - Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Medal

Figure 21 - A personal collection

Gulf War Illness – It’s Real

Gulf War Illness or Syndrome is a very real set of effects experienced by many, the RBL’s own study suggests over 33000 may have been affected, it is not formally recognised though. Reasons may include the injections and NAPS tablets we received and took, the huge smoke clouds caused when Iraq set fire to oil heads (day became night and the air was thick with soot, awful to breath), and recent studies have suggested quantities of sarin gasmay be a factor. Many service personnel have taken their lives since the Gulf War, many suffer to this day with all sorts of symptoms including; chronic fatigue, hypertension, muscle pain, cognitive problems, reduced coordination, rashes, diarrhoea, skin conditions and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). For me I am convinced what later presented itself as Ankylosing Spondylitis, Reactive Arthritis, with a bit of Diverticular Disease thrown in for good measure, is a result of that period. I am lucky though, mentally I have had great support around me with my family, and physically the MOD doctors were great, that has continued with the NHS to this day, I love my regular injections! I am not stating this for any response or sympathy, I am stating it because someone you know who deployed on Op Granby may be suffering, and it may not be obvious, if any signs show, talk to them.

A very personal note forever etched in my memory and linked to the Gulf War

En route back to Saudi I learned that my Mother-in-Law, Anne, has succumbed to cancer having had it for a second time. She had held on until the fighting was over, watching the news with my wife, Sandra, who had gone back home when I deployed due to her mother’s illness. Watching the news and endless repeats of DirtyDancing, a favourite. I was returned pretty quickly to Germany but then had to wait for a few days to get homedue to the compassionate grounds not being enough for an earlier return and I literally had no access to funds to buy a ticket myself. However, remember the best mate I mentioned before, he had returned home before me andimmediately volunteered to go from Scotland to N.Ireland for the wake and funeral. You never forget things like that, we are best mates to this day. He still laughs about a whole load of the women from the family rabbiting at him in fast ‘Norn Irish’, he had not a clue what they were saying.

I got home, gloriously happy to see my wife and 9 month old son, who of course didn’t recognise me, I had hardly seen him since Sep 90! Didn’t take long to bond again, now the lump of a man is a leading hand in the RN, how did that happen? I was not gloriously happy having lost Anne, the best Mother-in law I could have wished for, we missher even now.

Not helped when after a couple of days, the local RUC station called to say they knew of a threat to my life from the IRA, there were giving me a grace period because of Anne’s death (nice of them eh?), I raise this as it remained a constant threat for any trip home and few people realise it. We left not long after to return to Germany and our military adventure continued until 2012.

The End……for now

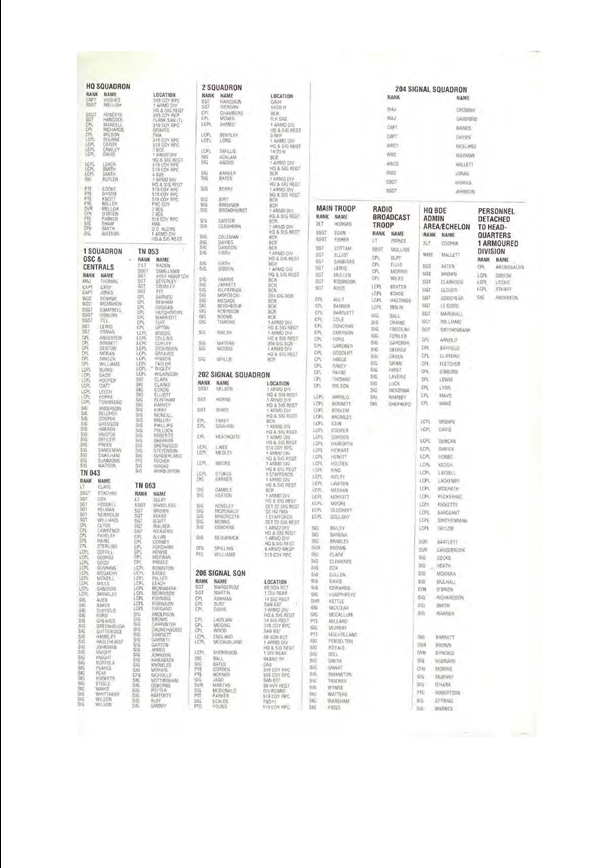

The Report Issued by my Regiment – 3ADSR