REMEMBRANCE

Quite often while the elements of Remembrance and Remembrance Services are widely recognised, people know less about their origins and history. The aim of this short series of articles is to give some of the background behind these deeply moving symbols and words.

THE ORIGIN OF THE POPPY EMBLEM

On the morning of 2nd May 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, Lieutenant Alexis Helmer of the Canadian Field Artillery left his dugout near the Canadian Brigade’s position on the canal just outside the town and was killed instantly by a German artillery shell. His burial took place later that day in a small cemetery near their position, next to the Dressing Station at what is now known as Essex Farm Cemetery.

In the absence of the Brigade’s Chaplain, his funeral was presided over by the Medical Officer, his friend and fellow Canadian Field Artillery officer, Major (later Lieutenant Colonel) John McCrea. He recited from memory what he could remember of the Church of England’s “Order of Burial of the Dead” and added a poem that he had composed in memory of his friend.

Lt Helmer’s grave was subsequently lost and he is remembered among the more than 54,000 commemorated on the Menin Gate in Ypres. Lt Col McCrae himself was to die of pneumonia in Northern France in January 1918 aged 45 and is buried in Wimereux Cemetery near Boulogne.

His poem was first published anonymously in Punch on 8th December 1915 and was almost certainly the origin of the adoption of the poppy as the symbol of remembrance.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields.

In McCrae’s own handwritten version at the end of the first line “blow” is replaced by “grow” and this is the version most often quoted.

THE EXHORTATION

On the 11th of November and again on Remembrance Sunday, people around the world will pause for two minutes silence to mark the very moment when, at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, the guns fell silent and the Armistice that ended World War One came into effect. This powerful Act of Remembrance commemorates all those who died or who were injured in conflict, regardless of nationality. As part of that commemoration a familiar refrain will be repeated but many aren’t aware of its origin.

The words used to begin the two minute’s silence, often accompanied by the haunting notes of the Last Post, were written early in The Great War by Lawrence Binyon, who was born in Lancaster on 10th August 1869, the son of a clergyman. After a classical education, including Trinity College, Oxford, he became a prolific author, poet and scholar, working at the British Museum in London. Although his works are not well known today, Binyon's reputation before the war was such that, on the death of the Poet Laureate Alfred Austin in 1913, he was among the names mentioned in the press as the likely successor, alongside others including Thomas Hardy, John Masefield and Rudyard Kipling; the post went to Robert Bridges.

A combination of age and his Quaker beliefs prevented Binyon from serving In World War 1 as a soldier. Nevertheless he volunteered at a British hospital for French soldiers as a hospital orderly, initially in France and later back in England, taking care of soldiers taken in from the Verdun battlefield. He wrote about his experiences in For Dauntless France (1918) and his poems, "Fetching the Wounded" and "The Distant Guns", were inspired by his hospital service.

However, it is for another poem that he is most remembered. Deeply affected by the opening of the Great War and the already high number of casualties of the British Expeditionary Force, in 1914 Laurence Binyon wrote For the Fallen whilst visiting the cliffs on the north Cornwall coast. The piece was published in The Times in September of that year, when public feeling was affected by the recent Battle of the Marne, the first major engagement of the War, in which there were 12,000 British casualties, of whom 1,700 died.

The fourth stanza of his poem has become the very centrepiece of the Act of Remembrance and you can hear his poignant words again at any of the many commemorative services that take place here in Spain this Remembrance Weekend:

With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children,

England mourns for her dead across the sea.

Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit,

Fallen in the cause of the free

Solemn the drums thrill; Death august and royal

Sings sorrow up into immortal spheres,

There is music in the midst of desolation

And a glory that shines upon our tears.

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted;

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.

They mingle not with their laughing comrades again;

They sit no more at familiar tables of home;

They have no lot in our labour of the day-time;

They sleep beyond England's foam.

But where our desires are and our hopes profound,

Felt as a well-spring that is hidden from sight,

To the innermost heart of their own land they are known

As the stars are known to the Night;

As the stars that shall be bright when we are dust,

Moving in marches upon the heavenly plain;

As the stars that are starry in the time of our darkness,

To the end, to the end, they remain.

Binyon’s words were among those set to music by Sir Edward Elgar in his last major work, “The Spirit of England”. Binyon himself died in Reading on 10th March 1943 and his funeral service was held at Trinity College Chapel, Oxford, on 13 March 1943. There is a slate memorial in St. Mary's Church, Alderworth, where Binyon's ashes were scattered. On 11 November 1985, Binyon was among 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey's Poets' Corner. The inscription on the stone quotes a fellow Great War poet, Wilfred Owen. It reads: "My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity."

THE KOHIMA EPITAPH

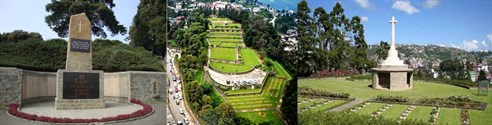

On the side of Garrison Hill in the Indian province of Nagaland, close to the border with Burma, stand two memorials to the 2nd British Division. Occupying the exact spot of the Battle of Kohima, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery commemorates the men who fought and the 2,337 who died there during the decisive battle to halt the advance of the Japanese 15th Army in 1944. Between April and June of that year the Division, part of ”The Forgotten Army” under the command of Lieutenant General Bill Slim (later Field Marshal, the Viscount Slim) fought in and around the Governor’s Mansion, including hand to hand fighting on his tennis court, to prevent the Japanese attempt to cut the supply route to the British IV Corps at Imphal.

At the higher end of the cemetery, a memorial commemorates the 917 Hindu and Sikh soldiers who were cremated in accordance with their religious beliefs. The epitaph on the Memorial reads:

“Here, around the tennis court of the deputy commissioner, lie men who fought in the battle of Kohima in which they and their comrades finally halted the invasion of India by the forces of Japan in April 1944.”

At the lower end stands a simple monolith of local Naga stone topped with the customary Cross of Sacrifice, designed for the Imperial War Graves Commission after the First World War by Sir Reginald Blomfeld, who also designed the Menin Gate in Ypres. This second monument bears a bronze plaque with the inscription:

“When you go home, tell them of us and say, For your tomorrow, we gave our today”

These words, known as “The Kohima Epitaph”, are attributed to the poet and teacher John Maxwell Edmonds and are thought to have been inspired by an epigram by the Greek poet Simonides of Ceos to the fallen at the Battle of Thermopylae. Although most closely associated with a battle from the Second World War, they actually date from 1918 when Edmonds authored an item in The Times, on 6 February 1918, headed "Four Epitaphs" composed for graves and memorials to those fallen in battle – each covering different situations of death.

These words are now widely used in Acts of Remembrance for The Fallen of all conflict.

REMEMBERING THE FALLEN

On the Fourth of August 2014, in the small town of Saint Symphorien just outside Mons in Belgium, the world looked on as the assembled European Heads of State and Government gathered in the Military Cemetery, where they and the families of those buried there marked the beginning of World War One on the day on which 100 years earlier, Britain had declared war on Germany.

At Saint Symphorien, the bodies of 513 German and Commonwealth soldiers lay side by side, 105 of them unknown casualties. Side by side is not quite accurate as a description because Saint Symphorien is unusual, if not unique, for a military cemetery and not just because it contains roughly equal numbers of the graves of the soldiers of both sides. Originally a small stone quarry, they had to bury the dead where they could: so it lacks the symmetry and, more noticeably, the size of many of the cemeteries and monuments to the Fallen of The Great War. However, it is a deeply poignant place, containing the graves of the first and last Commonwealth and German soldiers to die in the war, stretching from 21st August 1914 right through to 11th November 1918. It is also the site of the grave of the recipient of the first of the 628 Victoria Crosses awarded during World War 1, Lieutenant Maurice Dease, Royal Fusiliers who was killed at Nimy Ridge, age 24, on 23th August 1914.

Such was the scale of the casualties of the war that repatriation of their bodies was simply impossible. Fabian Ware, a schoolmaster turned newspaper editor, was struck by the lack of an official mechanism for marking and recording the graves of those killed. He set about changing this by founding an organisation to make sure it was properly done. In 1915 both he and his organisation were transferred from the Red Cross to the Army. By October 1915, the new Graves Registration Commission had over 31,000 graves registered, and 50,000 by May 1916. Established by Royal Charter on 21 May 1917, Ware’s important work was to be continued by the Imperial War Graves Commission, which later became the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Alongside The Royal British Legion, the Commonwealth War Grave Commission plays a key role in Remembrance. It is currently responsible for over a million graves and countless memorials from both World Wars in 23,000 locations in over 150 countries.

On 11th November and on Remembrance Sunday, people all over the world will gather at these beautifully and lovingly maintained sites, some containing just a few graves, others containing thousands. Some will stand alone silently before the instantly recognisable uniform headstones, differentiated only by their inscriptions: with the national emblem or regimental badge, rank, name, unit, date of death and age of each casualty inscribed above an appropriate religious symbol and sometimes a more personal dedication chosen by relatives. Others may take part in a formal ceremony with the Cross of Sacrifice as its focal point, a simple cross embedded with a bronze sword and mounted on an octagonal base. It was designed by the architect of the Menin Gate, Sir Reginald Blomfield to represent the faith of the majority. In larger cemeteries, these ceremonies may take place around the Stone of Remembrance designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, who also designed The Cenotaph in London and the Thiepval Memorial. The geometry of the structure was based on studies of the Parthenon and steers purposefully clear of shapes associated with particular religions to commemorate those of all faiths and those of none.

Across Britain, the Commonwealth and the World, these simple yet emotive structures will be adorned with poppies in Remembrance of all those who have died in conflict, providing us today and those whom we remember with a link to Ware’s initial vision from one hundred years ago.

THE MENIN GATE - YPRES

Every night, the town of Ypres comes to a standstill at 8.00pm as the buglers of the Last Post Assocation take their place underneath the arches of the Menin Gate. The Last Post was first played here at the dedication of the Menin Gate on 24th July 1927 and sporadically at events after that. At the request of the townsfolk of Ypres, the ceremony began as a formal ceremony on 28th July 1928. It was their wish that the town should hold a lasting and fitting commemoration of the thousands of soldiers who died in and around the town during the First World War and this daily act of homage and remembrance has continued unbroken since then.

During World War 2, Ypres was occupied by German forces and the ceremony was moved temporarily to Brookwood Military Cemetery but on the very evening the town was liberated by the 1st Polish Brigade on the 6th September 1944, Joseph “Fred” Arfeuille, one of the old Last Post Buglers, played the Last Post under the Menin Gate at 6:00pm and Ypres once again became the proud custodian of this unbroken tradition. It is said that the retreating German troops, who were less than two kilometres away, could hear it being played.

Come rain or shine, in front of a crowd that may be thousands or just a handful, a few minutes before 8.00pm a deep, respectful silence will descend as the buglers take their place. At exactly 8.00pm, the haunting notes of the Last Post will echo around the Menin Gate’s impressive interlocked arches and, for one minute, all will be calm and still as those present remember those from across Britain and the Commonwealth who lost their lives in the First World War and other conflicts. As the words of the Ode of Remembrance and the Kohima Epitaph die away, wreaths will be laid and, after a final moment of silence, those present will take a few moments to pay their own respects to those commemorated here.

The Menin Gate was designed by Sir Reginal Blomfeld, a prolific architect of the era and a staunch supporter of the Imperial War Graves Commission, now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Blomfeld also designed the nearby Saint George’s Memorial Church, the town’s second but perhaps less well-known monument to the fallen. The Menin Gate commemorates the more than 54,000 who fell in the area and who have no known grave. It contains the names of 8 holders of the Victoria Cross, ranging in rank from Private to Brigadier: ordinary men, international sportsmen and Members of Parliament who gave their lives in the service of freedom. In fact, such was the scale of losses that Blomfeld’s design proved too small to record all the intended names. Consequently an arbitrary cut-off date of 15th August 1917 was chosen and the 35,000 who perished after that and who have not been recovered are remembered at Tyne Cot Military Cemetery just a few miles away.

The design itself is as simple as it is imposing, two barrel-vaulted arches at right angles, topped by a lion, the symbol not just of Britain but also of the town itself. The main inscription reads “Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam – Here are recorded names of officers and men who fell in Ypres Salient, but to whom the fortune of war denied the known and honoured burial given to their comrades in death". The Latin phrase means 'To the greater glory of God'. This inscription and others on its sides, were composed by Rudyard Kipling, whose own son Lieutenant John Kipling served in the Irish Guards. John Kipling was serving with the 2nd Guards Brigade of the Guards Division and was reported injured and missing in action in September 1915 during the Battle of Loos. His body was never found.